Decarbonising Asia, a work in progress

It is often said that the journey of a thousand miles begins with but one step; and for Asia, this statement rings true with regards to the region’s push toward decarbonisation.

Driven largely by consumer demands for a cleaner energy system and investor pressures for reliable financial, as well as environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance, the decarbonisation race is on.

The Southeast Asian region is one of the fastest-growing regions in the world, with increasing populations demanding ever more in resources needed.

In fact, according to a report published by Climate Analytics, fossil fuels – which increasingly contribute to global carbon emissions and put economies at risk of locking into carbon-intensive energy infrastructure – remain the key focus in the development of energy infrastructure.

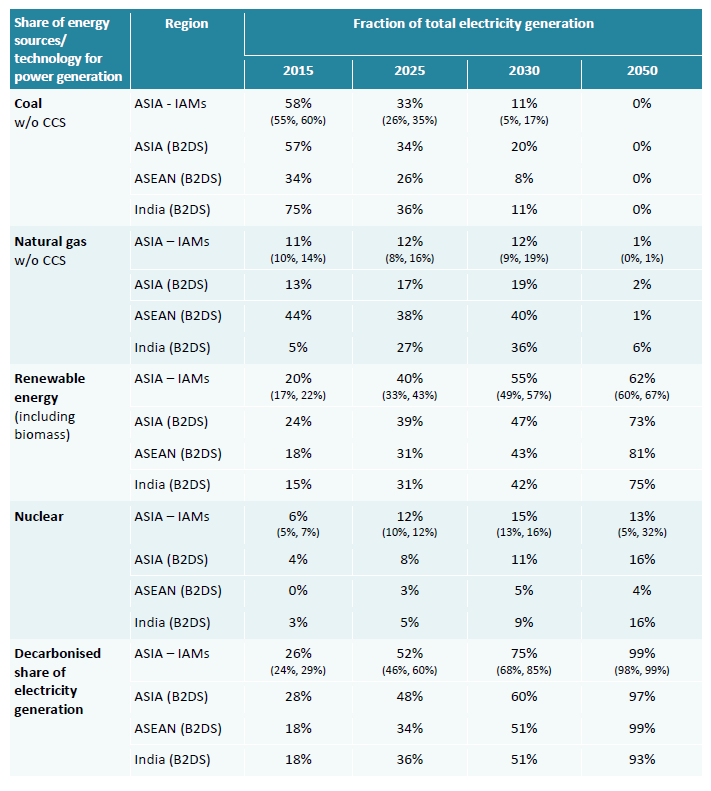

However, that seems set to change. In the Climate Analytics report, models suggest that there will a substantial decrease in the demand for oil in the Southeast Asian region, while India will experience an increase in this demand.

Likewise, gas use is projected to increase until 2030, before decreasing by 2050.

This seems to be in line with the push towards decarbonisation that the petrochemical industry has observed of late. A number of companies are already taking bold action, but will the industry be able to achieve its 2050 goals?

Little Red Dot making a big splash

Looking to Singapore as an example, the Garden City has made strides towards increased decarbonisation efforts, recently setting up a Maritime Decarbonisation and Autonomy Centre of Excellence aimed at focusing on the digitalisation and decarbonisation of Southeast Asia’s maritime sector.

Helmed by DNV GL, a recognised advisor for the maritime industry, the centre will seek to meet decarbonisation targets set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which include cutting carbon emissions from international shipping by at least half by 2050, with carbon intensity reduced by 40% by 2030.

Similarly, Shell Singapore announced just last year that it aims to cut CO2 emissions by a third over the next decade, outlining a 10-year plan which will build on the company’s goal of becoming a net-zero emissions energy business by 2050 or sooner.

This transition involves providing low-carbon solutions for customers in sectors important to Singapore, such as shipping; for example, the Pulau Bukom Manufacturing Site will “pivot from a crude-oil, fuels-based product slate towards new, low-carbon value chains.”

Is it enough?

Asia is doing its best to aid decarbonisation efforts – the Indonesian government has finalised a regulation aimed at encouraging more investment in the renewable energy sector, with a lofty goal of upping renewable energy sources from 9% to 23% by 2025.

Tokyo is speeding up its discussions of decarbonisation policies to meet 2050 climate targets. Honda Motor Co. recently said it will stop selling new gasoline-powered vehicles, including hybrids, worldwide by 2040, becoming the first Japanese automaker to set such a goal in response to the global trend of decarbonisation.

On top of that, the global demand for hydrogen is expected to enjoy rapid growth, with demand in China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore potentially hitting 11 to 56 million tonnes by 2040.

However, the question remains: Is this enough?

Southeast Asia has made progress in shifting to more sustainable energy sources, but must take care not to undermine its own efforts.

More can – and must – be done, if Asia is to make a serious headway towards curbing the region’s carbon emissions.

Towards the new circular economy

Increasingly, markets are taking a closer look at the methods employed by companies in ensuring that they adhere to science-based targets, and develop effective strategies for risk mitigation and carbon abatement.

The emergence of a low-carbon, circular economy is now possible, and many governments and regulators are starting to show their support.

It may be slow going at first, but this movement is likely to pick up speed; and with time, by-products and other waste products of production processes may be seen more as resources that can be reused or reutilised for other forms of economical value.